A Failure to Protect Girls in the System

The Foster Care System’s Broken Promise to Girls and Young Women

This newsletter was exceptionally difficult to write, for two primary reasons. First, as opposed to my entry on the experiences of boys in foster care, I don’t have the necessary lived-experience to contextualize the data I will be discussing below. I, obviously, cannot write about how it feels to be a girl raised in the system. Some might say that this is a reason to not write this particular newsletter, but frankly, I would feel as if I was doing a tremendous disservice if I didn’t use this platform to write about the experiences faced by 49% of those within the system. Nevertheless, it is a challenge, as I feel personal narratives augment statistical data.

Second, a significant portion of the academic literature on this subject focuses strictly on just a handful of issues, with the most prominent being the experiences of teenage mothers in foster care. Undoubtedly, this is a vitally important topic, and warrants extensive coverage. Given that extensive coverage, I won’t be covering that subject here and instead write about the experiences of the actual foster youth, irrespective of their roles as mothers. That leaves a panoply of potential topics to discuss, and narrowing them down meant leaving so many important elements of this experience on the cutting room floor. So with these limitations in mind, I decided to focus on two subjects in this newsletter: AWOL and Abuse.

Before I start, if you haven’t had the chance, please fill out this survey! Next year I’m rolling out some new features and new content, and I’d love to get your input into it all. I should mention that this survey is anonymous, so if you wanted to give me a piece of your mind, I’d have no way of knowing who it was!

Going AWOL: Foster Girls on the Run

In one of my earliest placements, I had a 17-year-old foster sister. Let’s call her Cheryl. She arrived at the home a few months after I was placed there, and largely kept to herself. One day, I returned home from school and was greeted by an audience consisting of a police officer, a pair of social workers, and my foster mother. I walked into the living room and was immediately subjected to an interrogation, not by the police but by my foster mom.

"Did Cheryl say anything to you?” She demanded to know, without providing a shred of context. She did not, I responded, and was subsequently sent to my room. Over the next week, my foster mother would routinely pepper me with questions, suspicious that I was perhaps in cahoots with Cheryl. Through these questions and her absence, I pieced it together: Cheryl had run away. She left for school one morning and never came back. When they searched her room, my foster parents discovered that she had packed up most of her belongings — she didn’t have many — indicating that she left on her own accord.

My foster mother took it as a personal affront that Cheryl would abscond, just like that, and as such, she’d talk about it constantly at the dinner table, speculating on where she might’ve went and why she chose to dip. All I remember my foster mother saying, over and over again, was the phrase “that damn boyfriend of hers.”

But after a few months, Cheryl’s name was never mentioned again, her room was filled with another kid, and life went on. I never did find out what happened to Cheryl. I did, however, learn that Cheryl’s situation was a reflection of a much broader trend: young women in foster care face an increased risk of going AWOL (Absent Without Leave).

Prior to digging into the data, I would’ve bet $100 that it would be young men that were more likely to run away, given that boys are more likely to engage in risky behaviors — substance abuse, fighting, engaging in criminal activity, etc. But I would’ve lost that $100.

Despite making up less than half of the children in foster care, girls were significantly more likely to run away from home. Between 2012 and 2017, they made up approximately 61% of runaway foster youth. But why? What’s driving so many girls to run away from foster care?

Well, numerous explanations have been offered, and each of them sound plausible to me. Many of these runaway foster youth have experienced multiple, deeply traumatic events, such as “death or incarceration of family members, sexual assaults, miscarriages, giving birth, and having a child removed.” Another study — albeit a bit dated, from 2002 — posits that there are three possible explanations for why girls in foster care run away:

They are more attached to their birth families and thus more prone to return to them by any means necessary.

They’re more likely be in a romantic relationship with someone in their communities of origin and thus more likely to run away to be with their partners.

Girls might take off to go and care for the folks in their lives, such as a parent struggling with substance abuse or a sibling being abused.

Another contribution to this phenomenon is something that is, tragically, bound up with the foster care system: trafficking. Some dated papers seemed to use the term “prostitution” interchangeably with “human trafficking”, which I won’t be doing here. But there is data supporting this theory. According to National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), approximately 19% of reports of runaways from foster care are “assessed to be likely victims of sex trafficking.” Of these reports, 29% involved girls and 3% involved boys. I will write a whole newsletter on this topic, so I’ll leave it here for now.

I wasn’t able to track down a more up-to-date, qualitative study that reassesses why young women might run away from the system, and I’d like to see such a study before I draw much firmer conclusions on what’s driving this trend. What I will say is that anecdotally, I have met women who ran away from the system during their youth and at least some of the findings above comport with their experiences. Some stories I heard:

One young woman reported time and time again the maltreatment she was experiencing at her foster home, and these reports went unheeded. So she left.

Another spoke of being moved three cities away from the school she was attending, with classmates she’d known for years. She ran away and lived with her best friend.

Yet another ran away again and again and again, to be back with her mother and siblings. She said told her social worker she’d continue doing so until she was legally reunited with her family, who just didn’t have the requisite number of bedrooms to take her back.

It is easy to shake one’s head and tsk tsk this decision to run away, but from the perspective of the child running away, the decision likely isn’t a difficult one to make. If you feel the system isn’t a source of love, you seek out those sources, wherever they may be. If you feel like the system isn’t protecting you, you seek a place that will. To reduce the supply of children running away, we need to reduce the demand for it, and that entails keeping kids safe.

Violence Against Girls and Young Women in Foster Care

Across a variety of dimensions, so many girls in foster care are left woefully unprotected. I can cite a heartbreaking list of statistics supporting this claim, but let’s start with the most galling one: 19.5% of girls report experiencing sexual abuse while in foster care. To emphasize this point: a fifth of girls in foster care have been sexually abused, while in the system. This is atop of the fact that females are substantially more likely to report having experienced sexual abuse prior to entering foster care, meaning that for at least some (and perhaps many) girls in the system, the system is exacerbating suffering rather than alleviating or addressing it.

I would be remiss if I didn’t note that while estimates vary, the 19.5% figure is roughly in line with the frequency of sexual assault amongst girls in the general population. So, in a system allegedly designed to protect those in its care, the fact that it doesn’t reduce the incidence of sexual assault should be a damning indictment on our current approach to protecting children.

(The same study found that 10.4% of young men report experiencing sexual abuse while in foster care, and young men are substantially less likely to report instances of sexual abuse.)

It is no wonder, then, that female foster youth have a greater likelihood of reporting symptoms consistent with current major depression, dysthymia, and PTSD, while also being more likely than males to report “past suicidal ideation and past suicidal attempts.” A team of researchers explicitly linked maltreatment with some of the above, finding:

Maltreatment (physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and sexual abuse) was associated with symptoms of anxiety, with a greater impact on girls compared to boys. The impact of neglect, specifically, on “depressive symptoms” was stronger for girls than for boys.

While physical abuse is more associated with externalizing symptoms (impulsivity, hyperactivity, and aggression) in boys, it led to more internalizing symptoms in girls, such as anxiety, worry, and social withdrawal.

These conditions create a multitude of adverse long-term outcomes. One study from 2009 found that compared to women in the general population, women with histories in foster care had the following characteristics:

More likely to have poorer health, more likely to be smoke, and more likely to experience obesity.

They had approximately three times the odds of having “probable PTSD.”

They were less likely to be educated, and more likely to be unemployed, living in poverty, and receiving public assistance.

It is clear from the above that a sizable portion of girls in foster care are not being protected and are not having their welfare safeguarded.

We Need A Better Way To Protect Girls and Young Women in Foster Care

Before I conclude, I wanted to briefly discuss the ways that girls and young women are perceived by caregivers, potential caregivers, and by the system as a whole. The issue, however, is that I have found very little qualitative data on the topic. For my previous post, I supplemented the absence of such data with my own personal experiences, but for obvious reasons, I am unable to do that here. If you know of any study on this subject, please send it my way!

With that said, in a very unscientific process, I did some digging on various forums, where foster parents and potential adoptive parents discuss the adoption process. In post after post, there seems to be a persistent concern about “false allegations” of sexual abuse. That is, potential caregivers are very concerned about being falsely accused of such abuse by their foster child. Again, this is an unscientific process and absent any study on the subject one shouldn’t draw too firm a conclusion. But if this fear is widespread, it indicates that the very people who are at most risk of experiencing sexual abuse — foster girls — are viewed as risks themselves.

Ok, I won’t speculate any further. I will just focus on what we know from the research: girls and young women in foster care are being harmed, and many are running away. I know that these are issues that advocates are struggling to solve, but I think that fixing them requires a wholesale transformation of the very conception of child welfare itself. We need to ensure that child protection doesn’t stop when a kid is removed from their parent, but rather extends into the system itself.

Incorporating the research that I conducted for my previous newsletter on boys and young men in foster care, I’ll just conclude this newsletter by saying the following: when you take a look at the data, it is clear that while boys and girls in foster care often have similar experiences, they face distinct challenges shaped by their unique circumstances and vulnerabilities. Caregivers, and potential caregivers, must understand that their individual perceptions (of the potential “problems” inherent with fostering a specific gender) can contribute to systematic inequalities and cause long-term damage. Any efforts to reform the system must grapple with this fact.

I’ll end it here, and thank you for reading! I will see everyone in 2025! Until then, please enjoy your holidays.

Current Read(s):

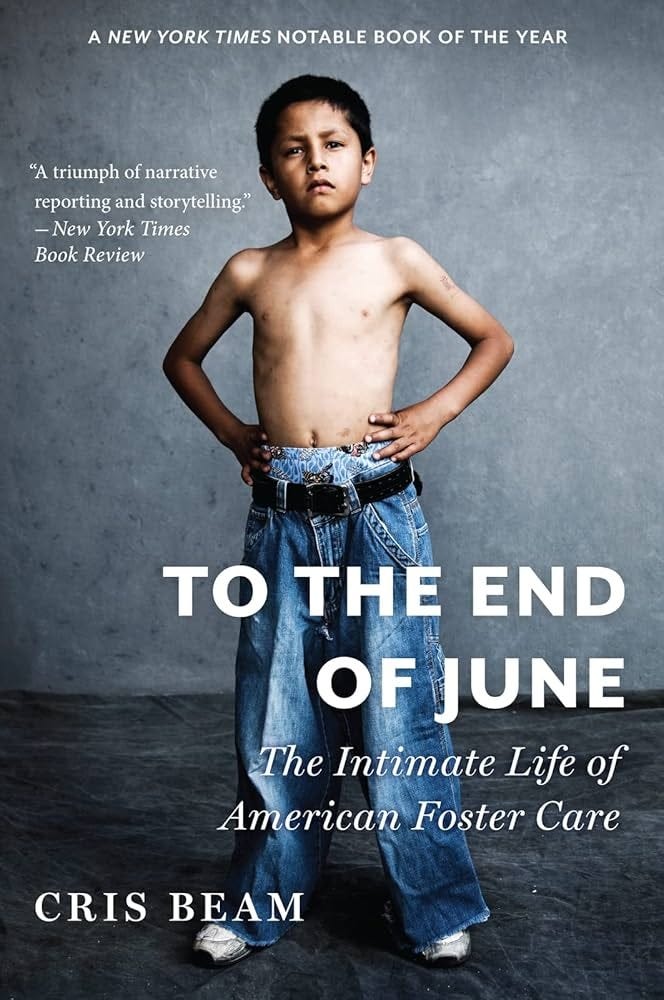

One of the last books I’m reading this year is actually a book I’ve already read. A decade ago, while serving in the US Navy, I was beginning to grasp about for ways I can make a difference on this issue. To help, I read some books, one of which was Cris Beam’s To the End of June: The Intimate Life of American Foster Care.

Beam — a foster mother herself at the time of writing this book — infuses her work with the voices of children actually navigating a system that is both responsible for raising them and nearly universally seen as being in a persistent state of crisis. For those who want to learn more about the system, this is a very accessible way to do so (in addition to maintaining a subscription with The Legacy Project)!

What’s going on in the world of child welfare?:

Sacramento Approves New Guaranteed Basic Income Program for Foster Youth (CBS) — I have a newsletter on basic income scheduled for next month, but let’s just say that this is a cool program that’ll undoubtedly help the foster youth in Sacramento.

Early Foster Care Gave Poor Women Power, 17th-Century Records Reveal (Science Daily) — Not so much about policy, but interesting nonetheless: foster mothers between 1660-1720 in England were tussling with their local authorities, and by doing so, exercised power.

Tennessee Law Provides Stipends for Relatives Caring for Children to Reduce State Custody Placements (WKRN) —Legislation in Tennessee will shore up a popular (and effective) program designed keep kids with relatives.

The Role of Illinois’ Fictive Kin Law in Reshaping Foster Care (Chicago Sun-Times) — A letter to the editor written by the director of the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services expounds upon the state’s efforts to place kids with kin, both biological and fictive.

After Times Investigation, Newsom Signs Bill to Crack Down on Parent Requirements in Child Abuse Payments (Los Angeles Times) — Legislation in California has been passed to regulate the provision of services that are often required for a family to reunify.

Better Prevention Efforts Keep Michigan Kids Out of Foster Care (Spartan Newsroom) — Michigan has enacted policies that have helped keep kids with their families.

Colorado Needs a Database to Track Foster Care Runaways, Task Force Finds (Colorado Sun) — It is well-known that children in foster care run away, but in Colorado, what is less well known is “why and how to stop it.”

Minnesota Justices Question White Couple’s Standing in ICWA Case (Sahan Journal) — Another attack on ICWA is underway, and this article dives into a couple of the ins and outs of this latest attack.

New Program at Fairmont State University Offers Housing, Education, and Support to Foster Teens (West Virginia Watch) — I’ll be keeping my eyes on this program as it is one that I thought about nearly fifteen years ago, when I was in the system. Maybe by getting foster kids college credits and support early, we can help boost college completion rates for this group. So very excited to see this program hopefully make a widespread impact.

Great read! Thanks for your work on this, Ricky