I’ve never been diagnosed with ADHD. One of my foster parents had me tested for it several times — for reasons that I believe were not entirely altruistic, which I have discussed in a previous newsletter — but none of the tests yielded a positive diagnosis. Nevertheless, given what I know about the relationship between the foster care system and ADHD, I sometimes wonder if all those doctors got it wrong all those years ago.

Why do I bring this up? Well, last month I read an article in the New York Times with the following headline: People With A.D.H.D. Are Likely to Die Significantly Earlier Than Their Peers, Study Finds”

Naturally, this article — and the study it describes — sent my wondering into hyperdrive. Late into the night I thought about the implications: tens of thousands of foster youth (and untold more former foster youth) have been diagnosed with ADHD. What does this mean for their lives, their futures? Then, in my late night bouts of dread, I’ve begun to think more broadly. Specifically, I realized I have been largely concerned with the quality of life for kids in foster care and not the quantity of life.

So, in this newsletter, I will delve a bit into this subject, exploring some ways in which involvement in the foster care system can adversely impact a person’s life expectancy (including a discussion of the aforementioned ADHD study). Brace yourself: it gets bleak.

Mental Health and the Foster Care System

As I discussed at length in several newsletters, children in foster care face a heightened risk of being affected by mental health challenges. I considered writing a long commentary in this section, but to be frank, I think the numbers speak for themselves. Let’s take a look at just ADHD, depression, and PTSD:

ADHD:

A 2015 study found that more than 1 in 4 children between the ages of 2 and 17 who were in foster care had received an ADHD diagnosis, compared to about 1 in 14 of all other children on Medicaid. A point must be stressed here: Medicaid serves eight in ten children in poverty. This, then, suggests that it isn’t simply poverty — which is often associated with involvement in foster care — driving these diagnoses.

The same study found that children with ADHD who were in foster care were also more likely to have another disorder, with about half diagnosed with “conditions such as oppositional defiant disorder, depression, and anxiety.”

Another study, from 2021, “found that the overall prevalence of ADHD in children in foster care was around 17%, a considerably higher rate than the general population, estimated at around 3.4%.”

Now, before moving on, I want to be careful and make three points:

A handful of these studies indicate that children in foster care are getting treatment for their ADHD, which we should celebrate!

I am not suggesting that foster care itself is causing children to have ADHD. Some of the conditions that contribute to a kid entering foster care — neglect, exposure to domestic violence, abuse, etc. — are contribute to a heightened risk of having ADHD. Undoubtedly, circumstances in foster care — placement instability, additional maltreatment, and more — play a role in several of these diagnoses, but I don’t want to suggest that foster care itself is to blame for the epidemic of ADHD cases.

Some scholars speculate that these high rates of ADHD diagnoses amongst foster youth is a “misrepresentation of ADHD symptoms that may be better explained by prior exposure to traumatic events among youth, or grief and loss.”

Depression:

Foster youth face an “increased risk of depression due to a variety of factors, including inherited vulnerability, child maltreatment, and the potential insults of the foster care system itself, including multiple moves and repeated relationship losses.”

One study found that depression (11.3%) was found to be the most prevalent mental health diagnoses and developmental disorders for children in foster care, followed by ADHD (11%), developmental and motor disorders (7.4%), and bipolar disorders (5.6%)

According to a study by Casey Family Programs, approximately 15.3% of foster youth alumni experienced a major depressive episode within a 12-month period. While this study is decades old now, it looked at folks who had left the foster care system, which is relevant to the point I’m making in this week’s newsletter.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD):

Always a shocker for me: “adults who had been children in foster care suffer post-traumatic stress disorder twice as often as U.S. war veterans.”

A study looking into foster care alumni found that 30% of respondents met “lifetime diagnostic criteria for PTSD, compared with 7.6% of a general population sample with similar demographics.

A team of researchers found that 19% of maltreated children placed in foster care had symptoms of PTSD compared to 11% of children who remained at home.

I could continue, citing dozens of more studies, but I think the point is clear: foster children are an incredibly vulnerable population with complex needs. Even if you don’t have any of the above, you can probably understand that struggling with PTSD or depression might contribute to a significant reduction in one’s quality of life. They also, unfortunately, might adversely impact the quantity of one’s life.

The Long-Term, Life-and-Death Consequences

Reading these statistics should break our hearts. So many foster youth are hurting, and so many former foster youth are still wounded — mentally, emotionally, and yes, even physically — from their time in the system. We should do whatever it takes to get these kids some help. This section should only serve to increase this urgency, for it reveals a sobering truth: these challenges don’t just shape the lives of foster youth—they shorten them.

I’ll keep this section short, because I want these numbers to hit you as hard as they hit me:

The study that I mentioned at the outset looked at 30,000 British adults with ADHD and found that, on average, “they were dying earlier than their counterparts in the general population — around seven years earlier for men, and around nine for women.”

Research from the University of Oxford suggests that recurrent depression can shorten life expectancy by 7 to 11 years, and a long-term study of over 3,400 adults found a link between depression and an increased risk of mortality.

Compared with people who did not experience trauma during their childhood, people with PTSD had up to three times the increase risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, and heart disease; up to 4.5 times of depression (showing how these conditions often overlap) and up to 12 times the increased risk of suicidality; and up to a 20-year decrease in overall life expectancy.

For the sake of comparison, let’s examine how certain risky behaviors affect life expectancy:

“Average cigarette smoking reduced the total life expectancy by 6.8 years, whereas heavy cigarette smoking reduced the total life expectancy by 8.8 years.”

“The years of life lost due to regular cocaine use was 10.3 years for an adult aged 31 years.”

The American Addiction Center has an Effects of Addiction Calculator, which estimates the effects of addiction on a person’s long-term physical health. Using the calculator, I found that someone who begins using methamphetamines three times a week at 25 could shave approximately 8 years off their life expectancy.

Just think about that last bit: using methamphetamines three times a week reduces life expectancy by about as much as having ADHD.

Prior to continuing, I should note that there is considerable overlap in all of the above. The conditions are themselves associated with certain risky behaviors — PTSD is associated with substance abuse, for example — and these studies are capturing all of this, and more. I recommend that you peruse the studies yourself to learn more.

These numbers might be a bit overwhelming, as depressing as they are, but we should always remember what they represent: real lives, real moments that could have been lived, laughter shared with friends, years spent with family, milestones never reached.

With all this said, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the threats to a foster child's life in the here and now.

There Are Also More Immediate Risks

We don’t have to wait decades to see the myriad ways in which foster children are imperiled — the dangers are present today, threatening their health, safety, and well-being as you read this. Again, I can drown you in studies, but just a few are necessary to communicate the gravity of the situation. I’ll focus on suicide and the mortality rate of children already in the foster care system.

Suicide:

Research — based on hospital records, emergency room visits, and death reports — shows that children and young adults with a history in foster care face drastically higher risk of suicide attempts and deaths, with rates ranging from 2 to 6 times higher than those in the general population.

Suicide rates among youths in foster care are alarmingly high: there are 37.5 suicide deaths per 10,000 youths in foster care each year, compared to 8.3 per 10,000 in the general population. Foster youth were also three to four times more likely to attempt suicide, with 3.6% of them attempting it compared to just 0.8% of the general population. (Note: the study I’m referencing uses ‘person-years’, which is a term used to quantify the amount of time that participants in a study were at risk. I believe I translated the term correctly, but for the medical folks reading this, feel free to correct me.)

A recent California study found that at age 17, just over 40% of youth had considered suicide, and nearly one in four attempted it. These rates far outstrip the general youth population, with 11.9% and 1.9% of US young adults (between 18-25) reporting suicide ideation and attempts, respectively.

Atop of all this, a 2020 study found that “children in foster care are 42% more likely to die than children in the general population, largely irrespective of race or age.” Worse yet, while deaths among children overall has decreased by 5.2% between 2003-2016, deaths of children in foster care remained steady. The study’s lead author added the following context:

“Importantly, our study does not conclude that foster care itself is contributing to the observed mortality differences. There are multiple factors that may have influenced our findings. Even when first entering foster care, these children have experienced many adverse experiences and have more medical and mental health needs than their peers. And once in care, children may face barriers to getting adequate health care—from incomplete medical records, to frequent placement changes, to challenges with consent among caregivers. It’s logical to conclude that these health and social disparities—among other challenges—are contributing to the concerning difference we saw in mortality rates. Yet, we need more data in order to inform evidence-based policy solutions to correct these trends.”

Taken together, we see that foster children are marked by danger and risk, in their day-to-day existence and over the course of their lives.

“We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now.”

We have work to do. There are literal lives at stake, both now and in the distant future. We need an all-hands-on-deck approach to supporting children and adults, especially those with histories in foster care. Every moment counts, and each intervention has the potential to both improve and extend a child’s life.

Our work must begin long before children enter foster care. We cannot wait for families to experience a crisis before we intervene, and we definitely shouldn’t wait for it to be dismantled. We need to radically accelerate our shift to early prevention. This means ongoing investments in at-risk communities, providing robust, concrete support for struggling families, and provisioning comprehensive mental health services, healthcare, and affordable housing for all who need it.

For children already in the system (and for those who might need it in the future), the time for half-measures has long passed. It is time the system realizes its transformative healing potential. This means doubling (or tripling) down on mental health resources, ensuring that every foster child has access to high-quality therapy, regular emotional support, and a stable, caring environment. Social workers need smaller caseloads, more training, and better resources to truly serve these children. Placement instability is a direct result of a broken system — we need to ensure foster children are not moved between homes at the whim of an overburdened system. I know from personal experience how crushingly lonely the system is; this needn’t be the case.

We cannot stop at just supporting those still in the system — we must extend the same commitment to those who have already left it. This requires bold, decision action: a massive, nationwide investment in mental health services, affordable housing, education, and job training for former foster youth. We need to carve pathways for former foster youth to lead healthy, stable, and successful lives. Put simply, we need to hold ourselves accountable to what happens to our children.

All this sounds like a lot. It is a lot. But a lot is required, for the stakes could not be higher. Every moment we wait, every hour we waste, is another moment of life stripped away from our country’s most marginalized citizens.

Current Read(s):

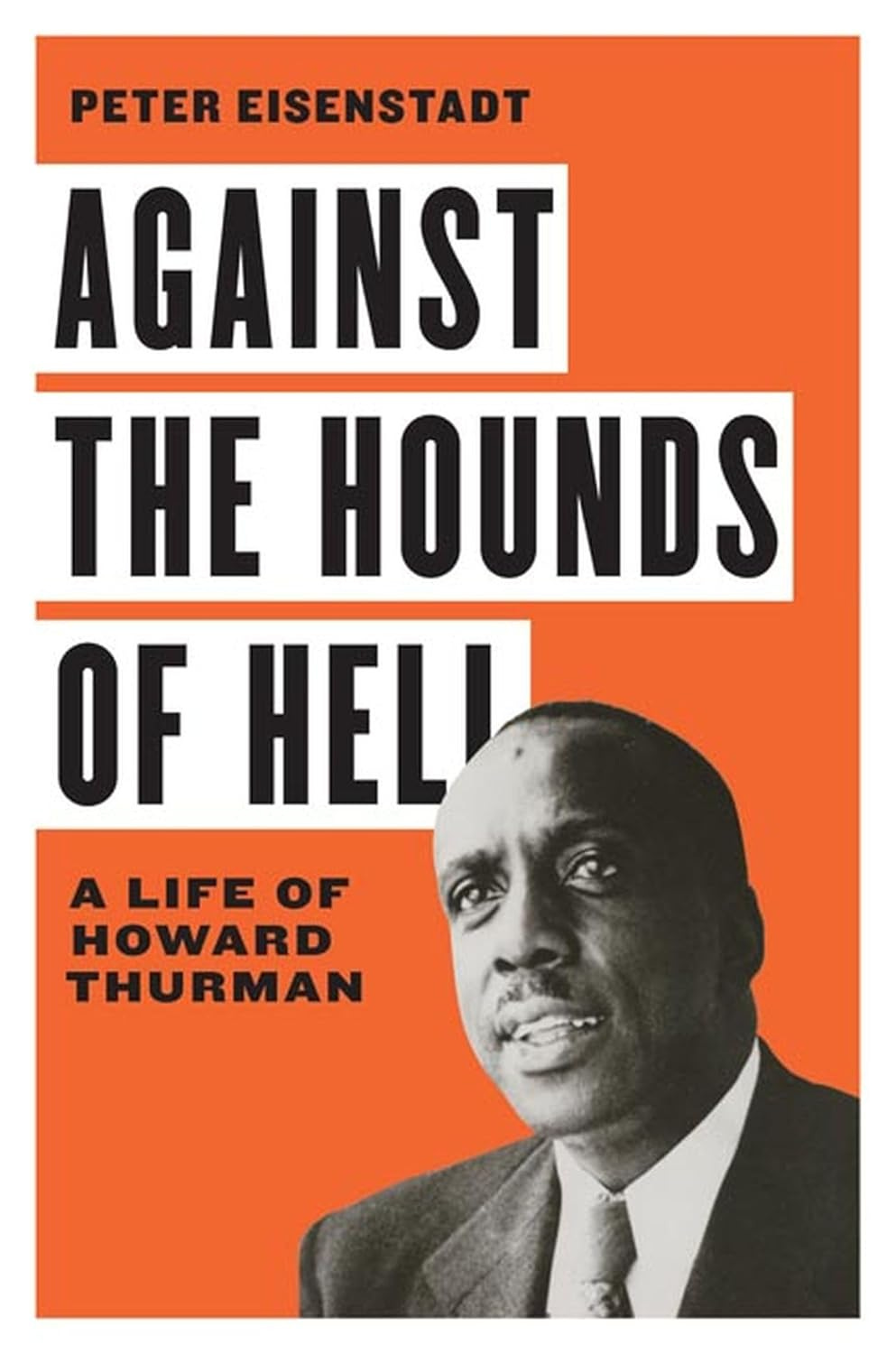

This week I’m working my way through Against the Hounds of Hell: A life of Howard Thurman. Thurman — a theologian, civil rights leader, mystic, and more — has long served as source of inspiration for me. He mentored Martin Luther King Jr., was the first African-American to meet Gandhi, and espoused a worldview that emphasized how nonviolence, empathy, and love are the forces that can dismantle systems of oppression and craft a better world. I’ve read much of his writing — with my favorite being Jesus and the Disinherited (a favorite of MLK’s as well, who read it during the Montgomery Bus Boycott) — but I have strangely read very little of the man himself. I’m correcting that now with this biography!

Notes from Abroad:

For this week’s installment, we’ll take a quick look at a study from Japan that explores the relationship between macroeconomic ‘shocks’ — specifically fluctuations in local unemployment rates — and and the incidence of child maltreatment. The study’s findings add additional evidence that economic instability directly impacts children: a 50% increase in local unemployment led to an 80% increase in reported child neglect cases and a 70% increase in child deaths, with particularly alarming spikes in deaths from unintentional injuries, drowning, and other external causes.

What’s Going On In the World of Child Welfare?:

An Inspiring New California Program Establishes Trust Accounts for Certain Foster Youth (Sacramento Bee) — A very cool program that I hope to see expanded!

How Some Christian Group Homes Avoid Florida’s Standards (New York Times) — A bipartisan group of state lawmakers are looking into allegations of abuse and misconduct by an organization that runs dozens of ‘maternity ranches.’

Ohio Foster-to-College Bill Aims to Bring Kids Out of System, Into Higher Ed, Career Tech (Mahoning Matters) — Even more good news! We love to see when states guided former foster youth down pathways of opportunity.

Pritzker Signs Law to Prioritize Placing Foster Children with Family Members (Capitol News Illinois) — And we also love to see states prioritize placing kids with kin rather than in the foster care system!

Nearly 900 Texas Children Are Waitlisted For a Mental Health Program Billed As An Alternative to Foster Care (Texas Tribune) — A program is only as great as the funding it has, and this story shows how tragic it is when an essential services is under-resourced.

Texas Lawmakers Consider ‘ICWA for All’ Bill That Would Set New, Higher Standards for Removing Children from Home (The Imprint) — I am very, very intrigued by this proposal. States should make active efforts to keep families together rather than reasonable efforts, and this proposal seeks to enact that more stringent standard.

California County Scorecard Reveals Statewide Struggles in Education and Foster Care (Children Now) — Kids are struggling in school at the moment, and foster kids are struggling even more: “just 21% meeting standards in English language arts, 11% meeting standards in science, and only 7% meeting standards in math.”

Parental Mental Health Biggest Cause of Child Protection Referrals in England (The Guardian) — Some more notes from abroad. Here in England, parental mental health has surpassed domestic violence as the most “commonly reported factor in social worker assessments into whether a child is at risk of serious harm or neglect.”

Arizona DCS Helping Foster Care Youth Hit the Road to Independence (KOLD) — Another state helping foster youth get driver’s licenses!

Child Welfare Reckons With The Harm of Investigations (The Imprint) — I wrote a bit about this nearly a year ago, but more folks are grappling with the harms of “seek and investigate” model of child protection, for these investigations are often intrusive, arbitrary, and isolating.

This Virginia Program Helps Foster Youth Get Degrees, At Any Age (WFAE) — Great, great news!