Introducing The Legacy Project

A Newsletter Dedicated to Transforming Child Welfare in America

My name is Ricky Holder, and I intend to utterly transform child welfare in the United States. This is my life’s mission, and this is the subject of this newsletter.

Perhaps I should begin by first briefly explaining what motivates this mission of mine.

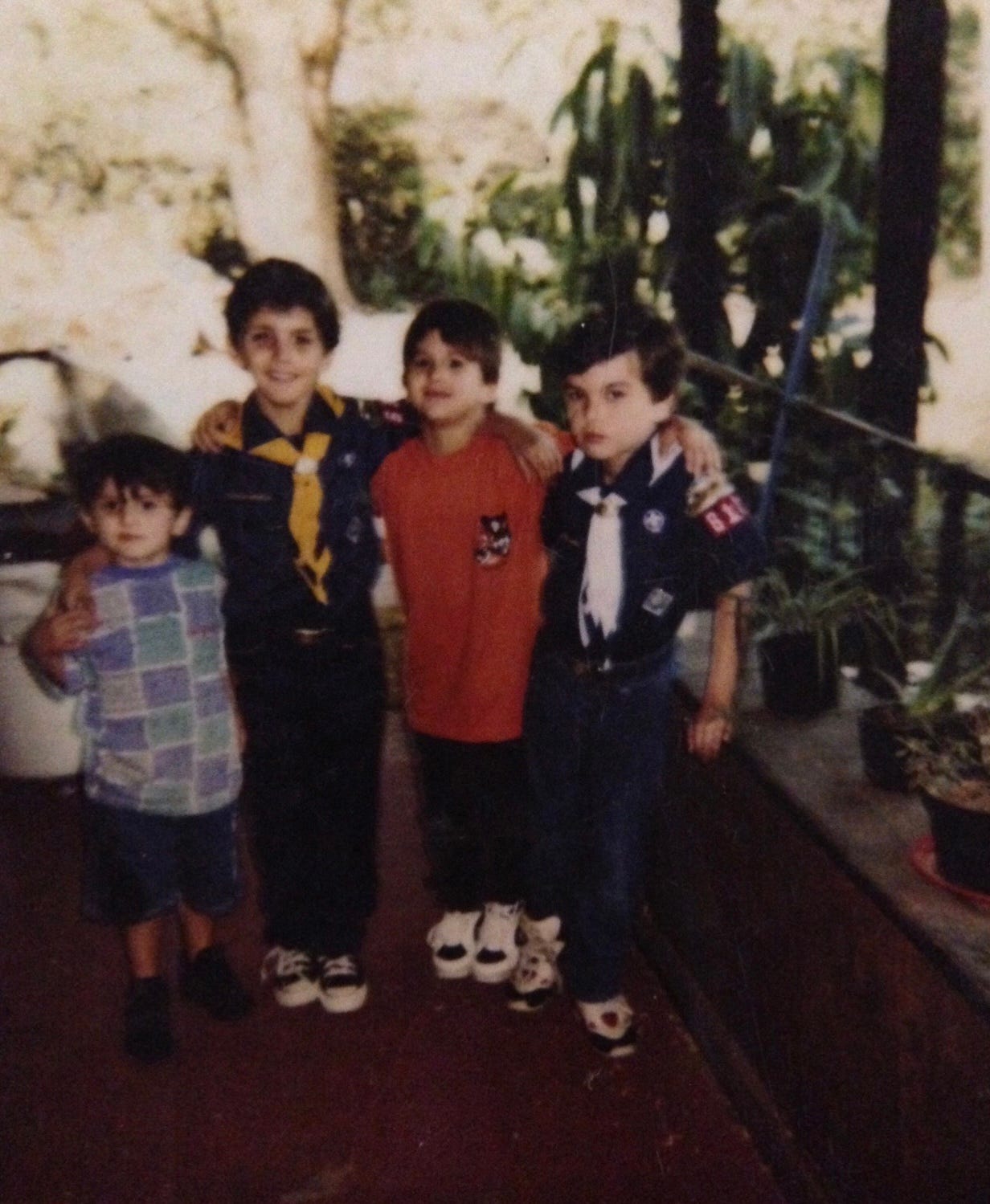

I was born in San Bernardino, California in the summer of 1992. Four weeks after my birth, my father abandoned my family, leaving my mother to raise four (and eventually, five) sons on her own.

She struggled. San Bernardino, for those unfamiliar with the city, has long been a punishing environment for low-income and working-class families. Our family was no exception.

I spent the majority of my childhood in abject poverty. For years we lived in a decaying home, bereft of running water, electricity, and plumbing. The windows had been boarded up, the outside graffitied and riddled with holes, and the lawn strewn with debris. Eventually, this decrepit refuge of ours caught on fire, which sent us on an odyssey throughout our city.

We lived in abandoned buildings, far-flung campgrounds and public parks, motel rooms and minivans, and more often than we’d’ve liked, the streets. At one point, we even briefly returned to the burnt shell of our former house, for even in its most dilapidated state, it was there we felt safest.

Our poverty was only matched by our terror, for we knew, as every low-income family in our neighborhood did, that our family faced an existential threat: Child Protective Services. For years we existed in a constant state of paranoia, fearing that every stranger on the street was CPS or that every county car that prowled the block was hell-bent on dismantling our family.

These conditions persisted for several years until one day, when I was nine years old, my mother was incarcerated. My brothers and I were placed in the child welfare system. More specifically, I was placed with a foster family and my brothers were placed in group homes.

My brothers would go on to live in countless group homes during their time in the system, and each of them would fulfill the statistical destiny that so often awaits children in the child welfare system.

“Our poverty was only matched by our terror, for we knew, as every low-income family in our neighborhood did, that our family faced an existential threat: Child Protective Services.”

First, they became entangled in the juvenile justice system, then they left the system and became swiftly entrapped in the vicious cycle of poverty, addiction, homelessness, and incarceration. Each of my older brothers would vanish for months and years on end, and when they’d resurface, I’d see that the bright-eyed boys of my youth had grown into broken men.

As for myself, I’d spend ten years in the foster care system. During that period, I moved seven times, from home to home to home. My mother was incarcerated in Chowchilla, California which was eight hours away. I had dozens of social workers and several families. I would move schools and communities so abruptly that I rarely had a chance to say goodbye. I spent a decade like this, experiencing constant heartache and loss.

“Each of my older brothers would vanish for months and years on end, and when they’d resurface, I’d see that the bright-eyed boys of my youth had grown into broken men.”

As my decade in this brutally broken system neared its conclusion, I became confronted with what every long-term foster kid must eventually face: emancipation, or “aging out.” “Aging out” was a mythic time that I had heard about from my earliest days in the system. Time and time again, I remember being told the “black bag” story, which goes as follows: when you turn 18 and graduate high school, you come home from graduation to find all your belongings in black bags on the curb in front of your foster home.

This wasn’t just a story to me, for I had watched each of my brothers age out into instant homelessness and I knew so many other foster youth who did the same.

(Fortunately, now, this doesn’t happen as frequently because many states, including California, have extended foster care until age 21. This law, however, went into effect January 1st, 2012. Unfortunately for me, I graduated in May 2011.)

So, on a whim and in a panic, I placed a call to the local Navy recruiting office two months prior to graduating high school. A week later, I enlisted in the United States Navy.

I served my country as an Information Systems Technician for six years, first in Norfolk Virginia, and then ultimately in Yokosuka, Japan, where I was stationed aboard a guided-missile cruiser.

It was during my service in the US Navy that I stumbled upon the purpose I outlined at the outset of this post. I spent many a night out to sea deep in thought, thinking about my childhood, my family, and the child welfare system. I was haunted by a series of questions:

How did it come to pass that I was serving my country, while virtually my entire family was serving time behind bars?

Why did so few foster youth emerge from the system unscathed?

Why did I make it out?

These questions, and so many others, led me to arrive at one unmistakable conclusion: I was so incredibly fortunate. A cursory glance at the statistics (statistics that will feature prominently in future newsletters) communicated to me that if you replayed my life 100 times, 97 times I wouldn’t have been on that warship serving my country but rather would’ve been destroyed by a system that destroys so many.

I realized that having been so fortunate to have escaped the circumstances of my youth, I must dedicate my life to ensuring no family suffers the same fate as mine, that no child has their future dictated to them by luck and luck alone, and that the child welfare system must be completely reimagined.

Armed with this realization, I separated from the US Navy in 2017. Since then, I’ve kept extraordinarily busy:

I married my high school sweetheart Leslie.

I attended Foothill College, a community college in the San Francisco Bay Area.

This past June, I graduated from the University of Chicago with a degree in Public Policy.

Now, I am pursuing an MPhil in Comparative Social Policy at the University of Oxford, as a Marshall Scholar. While in England, I’ll be studying the child welfare systems of multiple advanced countries, searching for insights to aid me in my life’s mission.

And so, that was my story in brief, and I told it for two purposes.

First, I wanted to firmly establish my credibility. What I will be discussing in future newsletters — poverty, homelessness, the child welfare system, family separation, trauma, and so much more — I have a tragic familiarity with, and this familiarity has been augmented by my various academic pursuits.

Second, the purpose of telling a story like mine is to highlight the centrality of storytelling itself in this newsletter. The child welfare system is amongst the least discussed and thus least understood issues in the United States, and this is partially because so few foster youth talk about their experiences.

There are of course the notable accounts that are highlighted in the media or are the subject of a bestseller or two, but I know from personal experience how difficult it is to tell folks about my time in foster care: I didn’t publicly start talking about my time in the system until I was 25 years old, after having separated from the US Navy.

“The child welfare system is amongst the least discussed and thus least understood issues in the United States.”

This silence was largely the result of the pain I experienced growing up, when classmates discovered I was a foster kid. I will never forget being referred to as an orphan or enduring speculation of why I was in the system: my mother didn’t love me, she was a “crackhead”, or that I was some type of deviant.

Now that I am open about my time in the system, I was dismayed to discover just how little the average person understands about the child welfare system.

Worse yet, I was shocked to learn that the policymakers I have met over the course of my undergraduate education — state legislators, members of Congress, Congressional and legislative staffers, policy analysts, and so on — have never critically thought about the system or have tragic misconceptions about it. This includes experts on subjects that are inextricably linked to the child welfare system: criminal justice, the opioid epidemic, the war on drugs, housing and homelessness, and so on.

Stories, I believe, are a neglected aspect of public policy, and many of the policies we have (both good and bad) are the result of the stories we tell about the people, places, and things these policies impact.

As such, this newsletter will be replete with stories to communicate that behind the damning statistics are children and families, to identify the self-defeating policies that erode the welfare component of the child welfare system, and to underscore that transforming the system requires transforming the narrative about the system.

This is The Legacy Project. As a subscriber, you are enlisted in this mission of mine, a mission that seeks to fundamentally reorient the US child welfare system, uplift and strengthen America’s families and communities, and forge the most pro-child and pro-future country in the world.

Thank you so very much for subscribing.

The next time you see me in your inbox, I will be doing a deep dive into mandatory reporting, a well-intentioned practice that often has devastating consequences for low-income families.

Until then, please be well!

In each newsletter, I will conclude with two additional sections, semi-related sections: “Current Read(s)” and “What’s Going On In the World of Child Welfare?”

The “Current Reads” Section is exactly what it sounds like: what am I currently reading? Those who know me know that I read a lot — between 50 and 60 books a year — and I am often asked to provide recommendations and reviews of the books that I read. Having never previously done so, I thought that this newsletter would be the perfect vehicle to let folks know what has my attention for the week.

The first book in my inaugural “Current Reads” section has little, if anything, to do with child welfare: J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Fellowship of the Ring, the first of three volumes of the epic novel The Lord of the Rings.

Now, I am typically not a consumer of the fantasy genre, but there is a specific reason why I chose to read Tolkien at this particular point in time: I am living in a house dedicated to him.

To make a long story short, Leslie and I are currently residents of Northmoor Road, in Oxford, the very street where Tolkien authored The Hobbit and most of The Lord of the Rings. Our house, overseen by the Oxford Centre for Fantasy, is dedicated to the Inklings, a group that included Tolkien as a member. While I am a tremendous fan of one Inkling in particular (C.S. Lewis), I have only a glancing familiarity with Tolkien’s works.

As such, in honor of my current living arrangement, I will be reading my way through three volumes of The Lord of the Rings.

The second section — “What’s Going On In the World of Child Welfare?” — is also rather straightforward: a compilation of articles, stories, and sources I find relevant to child welfare and family policy, with a bit of added commentary.

So, without further ado, here’s a brief roundup of recent articles, which I hope you find as informative or infuriating (or both) as I have:

Newsom’s veto lets California counties continue taking foster kids’ money (CalMatters) - In my home state of California, ostensibly the bastion of progressive politics, Governor Newsom vetoed legislation that would’ve ended the practice of counties using a foster child’s benefits (such Social Security checks) to pay for their care. While other states are banning this practice, California will persist in the outright thievery of some of the state’s most vulnerable citizens.

Biden-Harris Administration Announces New Actions to Support Children and Families in Foster Care (White House) - A new set of regulations issued by the Biden-Harris Administration that aims to bolster kinship care, protect LGBTQ+ foster children, and expand legal support for children and families at risk of entering (or have already entered) the child welfare system.

When Foster Parents Don’t Want to Give Back the Baby (ProPublica) - A devastating article that highlights ‘foster parent intervening’, a legal strategy used by foster parents to argue that a “child would be better off staying with them permanently, even if the birth parents — or other family members, such as grandparents — have fulfilled all their legal obligations to provide the child with a safe home.”

You Have the Right to Refuse CPS Entry: Texas Launches Miranda-style Warnings to Parents Under Investigation for Child Maltreatment (The Imprint) -In Texas, parents suspected of child maltreatment will now be informed of their rights during an investigation. This is a huge step towards rebalancing a system that is often tilted against low-income families.

I survived the foster care system. Dismantling it altogether is the only path forward (USA Today) - A former foster child argues for the abolition of the child welfare system, a system that she believes cannot be fixed and thus must be dismantled

Mental Health After Foster Care (The Imprint) - A former foster child and Army veteran argues for increasing access (and more importantly, funding) to mental health services for current and former foster youth.

‘No matter what I do, I’m not in control’: what happens when the state takes your child (The Guardian) - Written by Kelley Fong, a researcher whose work has had a tremendous impact on me, describes the myriad ways in which the child welfare system harms children and families (particularly Black and Native American families).

Let’s goooooooooo start the pod immediately ‼️