“There Aren't Too Many Families Willing to Take in Teenage Boys"

Some Reflections on the Challenges Facing Boys in the System and Society

“You better be careful, there aren’t too many families willing to take in teenage boys.”

I heard the above line literally hundreds of times during my decade in the system. It was said so frequently and by so many people — by most of my foster parents and virtually all of my social workers — that I swiftly internalized its underlying message: should whatever placement I was currently in fail, another family might not want me. Or, put differently, should I screw up, I’d be warehoused in a group home, with other boys deemed too broken to foster.

It was a statement that served multiple purposes: as a warning, as a disciplinary tool, and as a lesson. First, I was warned right at the outset — at nine years old — what the lay of the land was for kids like me. Second, any time I stepped out of line — no matter how minor the infraction — this statement was brandished about as a way to discipline me. And third, this was a lesson — a foundational truth about the system — teaching me that child welfare was contingent on age, gender, and behavior.

What a thing to say to a nine-year old, mere weeks after being separated from his family. What a system we have that explicitly communicates to teenage boys that they are damaged goods. And before you ask, yes, over the years I have spoken with a not-so-insignificant sample size of men with histories in the foster care system and the majority of them were told the exact same thing. I’d wager that boys in the system heard this statement far more often than they heard someone tell them “I love you.”

Earlier this year, I read Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male is Struggling, Why it Matters, and What To Do About It by Richard Reeves. It was a devastatingly informative book — it made President Obama’s summer reading list — detailing the variety of ways in which boys and men are struggling in today’s America. The author’s central contention is that while we have made considerable progress in crafting more opportunities for women and girls (and he states repeatedly that there is much more progress yet to be made), men and boys are falling further and further behind, especially for those at the bottom end of the socioeconomic ladder.

Ever since I finished this book, I have thought about writing this newsletter. I have long said that the foster care system serves as a sort of funhouse mirror for society, as it reflects and magnifies the country’s inequities. This is the case with the plight of boys and young men in foster care, whose struggles are exacerbated due to their involvement in the system. But I felt a newsletter might not be up to the task of covering such a subject, so I put it off.

But no longer. Today, I will be reflecting on the challenges that boys and young men face in the foster care system, utilizing a collection of statistics and an army of anecdotes. It might not be the most seamless of newsletters I’ve written, but I want to touch on a variety of points that underscore one central conclusion: boys and young men in foster care are struggling, and we need an all-hands-on-deck approach to alleviate their suffering.

And to be abundantly clear: I am not saying foster boys have greater challenges than foster girls, only that they have different challenges requiring distinct solutions. To demonstrate this, in the next newsletter, I will cover the range of challenges and traumas that girls and young women experience in foster care, as well as the variety of ways in which the system fails them. Given that I have personal experience as a boy in foster care, I thought it was more appropriate to begin with this particular discussion.

Let’s begin, focusing on three subjects: the impact of family structure on boys and young men, the experiences and outcomes of boys in foster care, and the lack of involvement of men in the child welfare system.

Boys from Broken Families

The tragedy of the statement I began this newsletter with is that boys benefit more from placement with families and are more adversely impacted by the destabilization of families, relative to girls. Let’s start with the latter: boys are disproportionately harmed when their families struggle, and especially when their families fall apart. Let’s take a quick look at the studies:

Boys born to low-income and marginalized families experience higher rates of disciplinary issues, lower academic achievement scores, and fewer high school completions than girls from the same background.

Boys with incarcerated fathers experience nearly twice the level of aggression compared to girls, and they uniquely face attention problems. Boys, particularly those who lived with their fathers prior to incarceration, often struggle to meet behavioral expectations both at home and in school.

Family instability is positively associated with boys’ behavioral issues at age five. Further, in general, transitions in family structures have been found to be more consequential for boys, perhaps because “levels of cognitive and socioemotional development during early to middle childhood tend to be relatively lower for boys than for girls,” which suggests boys “may adjust to family structure transitions at a slower pace than girls.” All told, boys demonstrate greater externalizing behaviors — such as aggression, stealing, defiance, etc. — as a result of family instability, relative to girls.

I should be clear: several of the studies above showed that family dysfunction and disintegration have deleterious effects on girls as well. But, for one reason or another, boys seem to be more sensitive to family structure.

Tragically, many of the challenges I listed above are associated with the same conditions that lead a family to become involved in the foster care system. So the very same circumstances that stunt a boy’s cognitive and socio-emotional development are the circumstances most likely to lead to that boy being placed in foster care.

A Systematic Problem

Six years ago, I volunteered to become a Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA). This position — appointed by a judge to advocate for the best interests of a system-involved child in court — required thirty hours of training. I was interested in being the person I desperately needed during my teenage years (and, for that matter, who my brothers needed). Put simply, I was hoping to advocate in court on behalf of young men in the foster care system. I knew this was a demographic that was balanced on a razor’s edge: a push one way could lead to destitution, while a push the other way could give them a fighting chance. I wanted to help give them that fighting chance.

During these weekly training sessions, I got to meet my fellow volunteers, and we’d chat over cups of coffee during breaks. I was curious to learn why folks were volunteering, and this curiosity yielded a few interesting insights. First, in my very unscientific poll of the room, it appeared that not a single person I spoke with was at all interested in advocating for teenage boys. Everyone, it seemed, had a particular image of a foster child in mind: a baby, a toddler, or vulnerable child below the age of ten.

Now, this is extraordinarily unscientific and likely doesn’t reflect the preferences of CASAs, in that room or in the nation. But I do believe it is a perspective that comports somewhat with my own experiences in the system, and the statistics that undergird my experiences. Namely, a ton of folks tend to view younger foster youth much more sympathetically. Teenagers — and particularly teenage boys — are either ignored or viewed unfavorably: as damaged goods, as too tough to handle, or as lost causes.

As far as I can tell, there isn’t any qualitative data that surveys foster parents on their preferences, or at least none that I can find. It is a general topic of conversation in forums (such as this one, this one, and this one), where foster and potential adoptive parents discuss the merits of fostering teen boys, or as one post put, whether teens “are all bad.” I’d posit that this phenomenon (of teenage boys being unwanted) is the system’s worst kept secret and I’d like to see some hard data on how folks think about it. Despite this lack of qualitative data, we can look at the revealed preferences of actors in the system to reach an inescapable conclusion: teenage foster youth are often the odd group out.

Despite making up only 51% of the foster care population, males make up 63% of group home placements. Of all children in group homes, 68% are between the ages of 14 and 17. Tragically, as with most things in the child welfare system, Black males are disproportionately represented in the group homes. Not only are they more likely to be placed in group homes, but males are also more likely to stay in group homes longer than girls, and experience more group home to group home moves.

All this communicates to me that fewer families are willing to take in teenage boys, meaning that many end up in group homes, which as long-time subscribers of this newsletter know, generally lead to worse outcomes. The tragic aspect of all this is that boys actually benefit more from being placed in families relative to girls, yet are less likely to be placed with families.

Now I get it: boys in foster care, statistically speaking, are more likely to exhibit behavioral issues, more likely to engage in risky behaviors, and are less likely to do well in school. This is in addition to the angst and rebellion that so defines one’s teenage years. I can imagine many foster parents just don’t want to deal with what they might see as a headache. But whenever I think about the ostensible reasons that might prevent a parent from taking a teen, I think of my older brothers, who entered the system and went directly into group homes. For whatever reason, no family even wanted to take them in from the get go, despite knowing nothing about them aside from the fact that they were teenagers. Again, the message this sends to a kid can only be harmful: you are unwanted.

It is no wonder why placement instability — when you move homes frequently — “increases the risk of delinquency in male foster children, but not for female foster children.” Boys — already so sensitive to shifts in family structure — become more likely to get in trouble the more times they move homes, or the more times they are told they are unwanted.

I won’t delve too deep into the outcomes for young men who emancipate from the foster care system, because in many ways they reflect the outcomes of young men generally, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds. But I’d encourage to check out a few longitudinal studies on the subject, where you'll see that former male foster youth are less likely to graduate college, more likely to report they have no one to turn to for tangible support, and more likely to experience homelessness.

I should emphasize again that no one — regardless of their gender — is spared from the risks of adverse outcomes associated with being involved in the system. All I want to underscore is that the systematic way in which young men are told — explicitly and implicitly — that they are lost causes has far-reaching consequences.

The Lack of Involvement of Men in the Child Welfare System

The people who had my back during the decade in the system were almost all women. It was female social workers and attorneys who often went above and beyond for me, who stood up to a foster parent, who kept tabs on my accomplishments, and who took a personal interest in my upbringing. Put simply, I wouldn’t be here had it not been the fierce advocacy of the women responsible for my case.

With that said, it is actually quite astonishing the gender disparities in the child welfare workforce and the child welfare volunteer community. Let’s take a gander at the latter, specifically focusing on the CASA organization I referenced earlier, who in addition to their advocacy in court, routinely meet with their respective foster child(ren) to build a relationship with them and serve as a consistent presence in their lives. The gender breakdown of the volunteer community is something to behold, demonstrated by the following random collection of statistics:

As of 2021, in the CASA of Morris and Sussex Counties (New Jersey), 90% of advocates are women and 10% are men.

As of 2023, in Kent County (Michigan), only 14% of CASAs are men.

As of 2021, in Kern County (California), only 22% of CASAs are men.

At the national level, a 2014 report found that only 18% of volunteers were men.

Atop of all this, approximately 83% of social workers are female. Now, an important question with an unsatisfactory answer: does it matter? That is, does it matter that there are so few male social workers and so few male CASA volunteers? My honest answer: I don’t know.

Here’s what I do know:

Boys tend to benefit from having positive male role models.

Young men benefit tremendously from having male teachers, and young Black men benefit tremendously from having Black male teachers. This is particularly the case for boys from low-income families.

I am curious, then, whether young men in foster care would similarly benefit if they could talk to someone who looked like them and who understood how it feels to be a young man. I wonder if their burden would be lessened if they had someone to look up to, or someone to guide them. I don’t know, but what I do know is that while there is a dearth of positive male role models, there is an excess of toxic male role models who are available (and all too willing) to lead young men astray, and this is particularly the case for kids in foster care.

I could tell horror stories, or rather, stories that break your heart, of promising young men I knew who were in need of guidance but were instead stuffed into group homes and told in a million and one ways that they were problems. Abandoned everywhere else, these kids either found community in all the wrong places — that is, with folks who led them astray, modeled toxic masculinity, and exacerbated their adverse outcomes — or descended into loneliness, as so many men often do.

I’m just speculating, I know. Having more male CASA volunteers might not have any impact whatsoever on young men in foster care. But, we have to do something to help these young guys out.

Painting A Path Forward

I left out a lot that I wanted to write about, but this is getting a bit long so I had to cut a ton. I’ll conclude by just saying two things:

We should stop telling boys in foster care about the lack of families willing to take them in — and especially stop using this statement as a disciplinary tool — and work damn hard to make sure a family is available for every kid who needs it. That means unleashing every tool we have in the toolkit, such as working to keep kids with their birth families whenever possible, connecting young men to the kin willing to take them in, or by placing them with a loving, qualified, and trauma-informed foster family.

If you are a man — or if you know a man — we need you to step up and volunteer. Place a call to your local CASA program office and chip in some time to help. We need you to guide our young foster men and model a positive masculinity for them. I promise you a few hours of your time a month can make all the difference in the world. I know 13-year-old me would’ve been appreciated it!

Let’s stop telling young men in foster care that they are disposable, and let’s start giving them the care they need.

Thank you for reading, and I’ll see you in a couple of weeks!

Current Read(s):

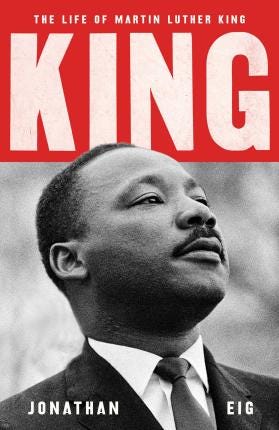

Martin Luther King Jr. has always been an intellectual, spiritual, political role model of mine. I’ve read every book he’s written — my favorite being Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? — in addition to many collections of his speeches and sermons. I have every book in the King Legacy Series, which I highly recommend for folks looking to learn more about MLK. So I’ve been eager to read Jonathan Eig’s King: A Life. It utilizes a collection of recently released sources — White House telephone transcripts, F.B.I. documents, letters, and more — to reconstruct MLK’s life, warts and all.

Very excited to keep reading through it, and I’ll be a bit sad when I wrap this biography up.

What’s going on in the world of child welfare?:

U.S. House Lawmakers Pass Bipartisan Child Welfare Legislation (National Association of Counties) — Some very important child welfare legislation just passed the house!

Adopted. Abused. Abandoned. How A Michigan Boy’s Parents Left Him in Jamaica (USA Today) — One of the craziest stories I’ve ever read: a kid was adopted and subsequently abandoned in another country. I urge you to give it a read.

Lawsuit Detail Troubles in Struggling N.C. Child Welfare System, as Officials Work to Make Changes (North Carolina Health News) — One of the key mechanisms in child welfare reform have been lawsuits, and that is precisely what we are seeing in North Carolina.

Kansas Foster Care Not ‘Capable of Making the Changes,’ Advocates Warn (The Beacon News) — Advocates in Kansas are alleging that the promises emanating from the settlement of 2020 lawsuit have not been met, and foster children in Kansas are paying the price for this failure.

Thousands of Foster Kids in California Could Lose Their Homes Amid Insurance Crisis (Los Angeles Times) — A crisis is brewing in California, where a well-intentioned law is threatening to upend placements for thousands of foster children in the state. I am still thinking through this issue myself, as it is very complex.

Dallas-area Foster Care Overhaul Off to A “Rocky Start,” Executive Admits (CBS News) — A major metropolitan area (consisting of 9 counties) in Texas privatized its foster care services, and things haven’t gone well.

Report: Roughly 13% of Children in NM Child Welfare System Experience Abuse, Neglect (KRQE News) — 13% of kids in New Mexico’s foster care system — meaning that they are in state custody or involved in the system in some way — are being neglected or abused.

Federal Judge Approves Historic Oregon Child Welfare Settlement After Emotional Testimony (Oregon Capital Chronicle) — Another state, another lawsuit. In Oregon, a lawsuit has been settled that requires the state to improve a system that has been criticized for a variety of its practices, such as shipping children to out-of-state facilities.