Turning the Tables on the 'Neglect' Script

Parents Aren't The Only Ones Capable of Neglecting Children

Let’s kick this newsletter off with a little thought experiment. Below, I’ll provide a definition of child neglect. With it, I would like you, the reader, to determine which of the provided behaviors constitute neglect.

Here’s how California partially defines neglect, drawn from a pair of statutes:

“If a parent of a minor child willfully omits, without lawful excuse, to furnish necessary clothing, food, shelter or medical attendance, or other remedial care for their child, they are guilty of a misdemeanor.”

“General neglect” means the negligent failure of a person having the care or custody of a child to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, medical care, or supervision where no physical injury to the child has occurred but the child is at substantial risk of suffering serious physical harm or illness. ‘General neglect’ does not include a parent’s economic disadvantage.”

I used California, but you could select any state’s definition of child neglect and while it might vary somewhat, it would largely identify the same behavior as neglectful. Ok, now, with this definition in place, let’s have you apply it to specific behaviors. Remember, the only information you have is the definition and what’s below. Without further ado, here we go!

A parent knowingly exposes their children to chemicals or pollutants that adversely impact a child’s development and produce long-term health challenges.

A parent fails to provide safe drinking water or adequate food to the child and does little to address this shortcoming.

A parent is cavalier about gun safety in their house in such a way that that it puts their children at risk.

A parent willingly sends one of their children to a well-resourced school and sends the other to one falling to pieces.

A parent fails to provide the necessary medical care, particularly for their young children.

A parent does nothing to protect their children from the elements, particularly extreme heat, which is known to pose a significant risk to a child’s physical health.

A parent fails to maintain safe and secure housing for their child, and does little to remedy the situation.

How’d you do? If you were operating strictly on the definition provided, then all 7 of the above behaviors would constitute child neglect. In each instance, the parent responsible would be subjected to an investigation, to an extensive intrusion by Child Protective Services, and would maybe even have their child placed into foster care. We can debate whether any of these interventions are sound or appropriate, but what we can’t debate is that no child should be subjected to any of the behaviors I just described.

I don’t think I’ve said anything very controversial thus far. Any reasonable person would be concerned for a child experiencing any of the above and would want the relevant authorities to remedy their situation. In many cases, parents who subject their children to these conditions — or rather, allow such circumstances to develop — are seen as being willfully negligent, according to polling. Y’all know my position on this framing, but this newsletter isn’t about that. Instead, I want to highlight something else, namely that all of the above occurs everyday, at a magnitude that boggles the mind.

Every single day in this country, millions of children go hungry or drink tainted water. Every single day in this country, millions of children are sent to schools that are inadequately funded and adequately failing. Every single day millions of children are exposed to extreme heat, resulting in tens of millions of visits to the emergency room. Every single day millions of children breathe in toxic air, or play on playgrounds a stone’s throw away from sources of harmful pollution.

Yet this behavior is never considered neglectful, because the blame cannot be neatly packaged and laid at the feet of a single individual. Everyday, children are put at a “substantial risk of suffering serious physical harm or illness” as a result of governmental action, and perhaps more often, governmental inaction, yet this is never considered neglect. We, as a society, are overzealous in our prosecution of individual acts of child neglect, but are comparatively tame in addressing societal neglect. It is time we expand our definition of neglect to include all potential perpetrators, including society itself.

In this newsletter, I’m going to make the case for this shift in perspective by highlighting the litany of ways children are harmed by the policies, practices, and institutions that surround them. I intend on showing that in many instances, even the best of parents can’t protect their children from the harm imposed on them by the wider world. Let’s dig in.

An Environment Hostile to Children

Let’s take that first scenario above: A parent knowingly exposing their children to harmful chemicals or pollutants. Millions of children are breathing in toxic air not as a result of their parents’ actions, but due shortsighted decisions of policymakers. Let’s unpack this by way of example.

San Bernardino County — where I was born and raised — has been remade by the logistics industry, with one of the highest concentrations of warehouses in the United States. Every time I visit home it seems another dozen warehouses have sprouted up. There are more than 3,000 warehouses in San Bernardino County alone, and when combined with the neighboring counties (which collectively comprise a region called the Inland Empire), there’s an estimated 1 billion square feet of warehouses in the region. Needless to say, that’s a ton of warehouses, and what do warehouses bring with them? Diesel trucks.

According to folks at the University of California Riverside, these warehouses generate over 200 million diesel truck trips, which “in turn produce over 300,000 pounds of diesel particulate matter, 30 million pounds of nitrogen oxide, and 15 billion pounds of carbon dioxide a year.” Over 640 schools in the area are located within a half mile radius of a warehouse, and 139 of these schools are within 1000 feet. While kids are at recess shooting hoops or running around, truck after truck (after truck, after truck, after truck) are pulling in and out of warehouses right down the street, spewing their fumes into the air and eventually into those kids’ lungs.

I probably don’t need to tell you, but diesel particulate matter isn't great for a developing respiratory system. It burrows — yes, burrows — into the lungs, causing asthma, inflammation, and a litany of other respiratory illnesses. Over the long-term, exposure to air pollution increases a child’s chances of developing high blood pressure, cancer, asthma, and mental health disorders that adversely impact learning, memory, and problem solving.

To toss another datapoint atop the rest, one study compared the health outcomes of children at two elementary schools. One school was located approximately 500 meters “directly downwind” of the San Bernardino Railyard — a major source of diesel emissions — and the other was seven miles west. The authors found that the school near the rail yard saw a “59 percent increase in reduced peak expiratory flow, an indication of poor lung function.”

Given that wide swaths of this area is classified as low- and middle-income, it would appear that the more than $1 trillion dollars worth of goods that flow through the region is facilitated by the destruction of the lungs of working-class children. We shouldn’t be comfortable with this, nor hand wave it away as a necessary sacrifice to keep the engines of commerce pumping.

I will just add briefly: this is not an anti-warehouse screed. I have dozens of friends who butter their bread as a result of the expansion of the logistics industry in my neck of the woods, as well as two close family members. Many of these folks have children, and absent the income they earn in the warehouse industry, they'd be hard-pressed to pay the bills. It’ll take another newsletter — and certainly not this one — to delve into the pros and cons, the ins and outs, of the warehouse boom, as well as how to make it better for all relevant parties. All I want to highlight is what is readily apparent to even the most casual observer: some forms of child harm are ignored and perhaps even accepted, and other forms are punished and penalized. Nobody, it seemed, consulted the children who’d be harmed when decisions were made to plop a mega-warehouse in their neighborhood.

Before I move onto the next section, I want to emphasize that the issue of pollution and environmental degradation isn’t restricted to San Bernardino. Here’s just a few stats that demonstrate how widespread this issue is:

A quarter of US children (18.5 million) live within 2 kilometers of toxic-waste sites that contain contaminants such as genotoxic carcinogens, which are known to be harmful to children and contribute to higher rates of cancer as adults.

People living in Louisiana’s infamous “Cancer Alley” — where petrochemical and fossil fuel plants pollute with impunity — have “low birth rates as high as 27 percent, more than double the state average (11.3 percent) and more than triple the US average (8.5 percent). Preterm births were as high as 25.3 percent…nearly two-and-a-half-times the US average (10.5) percent.

A study found that in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, even “moderate amounts of air pollution increase the number of children going to emergency rooms for asthma,” with Black children ages 6 to 11 most affected.

All told, we wouldn’t hesitate to drop the “neglect” label on a parent found to have exposed their kids to harmful pollutants, and many would demand a swift resolution to the issue. However, when billion dollar interests expose millions of children to pollutants, we seem to lack the right language to describe what is being done. It is neglect, perpetrated on a societal-scale, and we need to call it as such.

Want in the Land of Plenty

The definition I provided above stipulates that a parent who is unwilling or unable to provide their children the necessary shelter, food, clothing, supervision, or medical care is engaging in child neglect. If that’s the case, the United States is systematically neglecting millions of children across a range of dimensions. Rather than spell each dimension out in detail, I think it would be more impactful to firehouse you with facts of how the country is shortchanging its children:

A 2023 review of the American Board of Pediatrics workforce data set found that approximately 47% of U.S counties lack a general pediatrician and thus are categorized as a “pediatric health desert.” Only one-third of emergency departments are “at hospitals with substantial pediatric operations”; in the remaining two-thirds, the ER is the “only part of the hospital that treats children…[the staff] often lack specialized training in treating children.”

Millions of families live in food deserts. High-poverty and non-white neighborhoods have the least access to supermarkets and thus have fewer places to purchase nutritious foods. Folks living in rural and remote areas of the country — especially Native American and Alaskan Native communities — also lack access to supermarkets.

Between 2017 and 2020, 10.3% of children (roughly 7.4 million kids) experienced both water and food insecurity, up from 4.6% in 2005-2006.

51% of Americans live in a child care desert, defined as any “census tract with more than 50 children under age 5 that contains either no child care providers or so few options that there are more than three times as many children as licensed child care slots.” Furthermore, in all 50 states, the price of center-based child care for two children exceeded average annual rent payments by 25% to over 100%.

I wrote about housing a few newsletters back, so feel free to reference it for a more in-depth dive on the issue. But to be brief, there is a shortage of somewhere between 4 and 7 million homes in the United States, which has substantial implications on housing affordability for many families.

School funding disparities are rife in the United States, where having access to higher-quality education is contingent on being able to afford to live in higher-cost areas. School districts with predominantly Black, Latino, and Native American students receive approximately $2,700 less per pupil in government revenue than predominantly white school districts. In addition, the average difference between lower- and higher-poverty school districts is $4,119.46, a consequence of school funding emanating from local property taxes.

All of the above and more indicate that even a parent that checks all the right boxes, that does everything expected of them, could still be confronted with a range of deficiencies in areas critical to the upbringing of their child. A parent can make all the right decisions, but no decision save moving away can address the fact that they live in a food, pediatric, or child care desert. Moving away, I might add, is certainly not an option for so many Americans given the acute housing shortage in the areas of the country where these deserts likely don’t exist.

I’ll say it loud and clear: the children subjected to all of the above are being neglected, and the perpetrators are not the parents but the policymakers who know of these shortcomings yet fail to address them.

When Governmental Inaction Harms Children

Let us take another one of those hypothetical scenarios I provided in the introduction: a parent leaves a loaded gun on their dining room table unattended, and a young child has access to it. Is that neglect? Between 82-99% of surveyed social workers found this to be neglectful behavior, if that informs your judgment at all. The implications are obvious: this is textbook neglectful behavior, for it puts a child at a “substantial risk of suffering serious physical harm.” We recognize it when we see it in this context, but we should also start slapping the neglect label (or perhaps something a bit stronger) on the continued failure to protect American children from gun violence.

It is an oft-stated fact but one so infuriating that it is worth shouting from the rooftops (and bolding in newsletters): firearms are the leading cause of death among US children. Bullets kill more US children than motor vehicles, cancer, poisonings, and drownings. Guns were responsible for 20 percent of all children and teen deaths for both 2020 and 2021. It is an issue and a growing one at that: the child firearm mortality rate has doubled from 1.8 deaths per 100,000 in 2013 to 3.7 in 2021.

Tragically, children in the US have substantially higher gun suicide rates compared to children in other wealthy nations. One study found that if the US child and teen suicide by firearm rate was the same level as Canada’s, over 1,000 fewer children in the US would have died in 2021 alone. This is bleak stuff.

I won’t wade into the morass of the gun control debate in today’s newsletter, but I will just reemphasize what I’ve been saying throughout this piece: our inability to get a handle on gun violence continues to put children at an increased risk of suffering harm. This is neglect, plain and simple, by any definition of the word.

Another instance in which inaction is harming children is the decades-long failure to address the harms of climate change, or more specifically, to protect kids from extreme heat, which is the most deadliest-weather related hazard in the United States. Babies and young kids are among the most vulnerable to heat-related illness, a tragic fact considering that in the US, approximately “36 million children are exposed to double the number of heat waves compared to 60 years ago, and 5.7 million are exposed to four times as many.” This heat isn’t just making life uncomfortable for folks; it is hurting children.

One study analyzed 3.8 million emergency department (ED) visits by children and adolescents over a 3-year period, using data from 47 children’s hospitals. They found the following:

“Their analysis showed an increased risk of children’s ED visits for any reason in association with extreme heat, compared with days of moderate heat. Associations were strongest among children of color and those without private health insurance. Extreme heat was most strongly associated with ED visits for heat-related illnesses, as well as with visits for other illnesses, including bacterial enteritis and ear infections.”

Our environment simply isn’t built to accommodate this heat, and this is especially the case for children. We all remember our days on the blacktop, smacking a tetherball or playing hopscotch. Blacktop, however, absorbs and retains heat, meaning kids these days are increasingly playing on a stovetop. Case in point: in 2022, researchers discovered that school asphalt temperatures reached 145 degrees during a 93-degree day in California’s San Fernando Valley.

Heck, a ton of kids aren’t even safe indoors: approximately 30% of school buildings in the United States do not have adequate air-conditioning. A 2024 article by the Federation of American Scientists referenced a September 2023 incident in New York where classrooms were getting up to 94 degrees and children were passing out as a result. If that occurred in someone’s home, Child Protective Services would be there in a hot-minute.

Everyday we fail to address these seemingly intractable challenges, more children are being hurt and even killed. We can’t strictly be concerned when a parent’s inactions lead to a child suffering. As a matter of fact, given the scale of the harm involved, we should be more concerned when policymakers refuse to act decisively on the issues that put children in danger.

Let Us Address All Acts of Child Neglect

We’ve either become numb to widespread child suffering in the United States, or chalk it up as something that just happens. Perhaps this is a consequence of our cognitive infrastructure as humans. It is far easier to become outraged at an individual inflicting harm on a child, just as it is easier for our hearts to break when learning of the plight of a single child in pain. But when millions of children are being harmed, when millions of children lack access to the basic necessities of life, and when there is not one entity or person to be blamed, it is perhaps harder to muster the same outrage. I don’t know, I’m just spitballing here.

What I do know is that our definitions of child neglect and child maltreatment are far-too-narrow. Neglected children are neglected children, regardless of who perpetrates the neglect. When the perpetrator is the government — when policymakers fail to get enough housing built, fail to address extreme heat, fail to provide affordable and available child care, and fail to keep the air clean — we should be especially angry given the sheer number of children affected. I am not advocating that we shift focus away from individual instances of neglect, or minimize them at all. We can walk and chew gum at the same time. We can make sure parents are doing right by their children while also fiercely holding society to the same standard.

Anna Gupta — of the Royal Holloway, University of London — wrote something about neglect that I’ve long found striking: “The construction of neglect is a problem that children need to be rescued from rather than one that their parents can be supported to address.” By reorienting the way we conceptualize neglect, we can move away from a paradigm that prizes punishment and towards one that centers support. By identifying governmental inaction as child neglect, we can be equipped with the language to hold policymakers accountable. If we can bring the state down upon a low-income parent, we can vote out a policymaker allowing child neglect to fester.

In sum, if the goal is to keep kids safe, we need to look at all sources of harm. Thank you so much, and I’ll see ya in a couple of weeks.

Current Read(s):

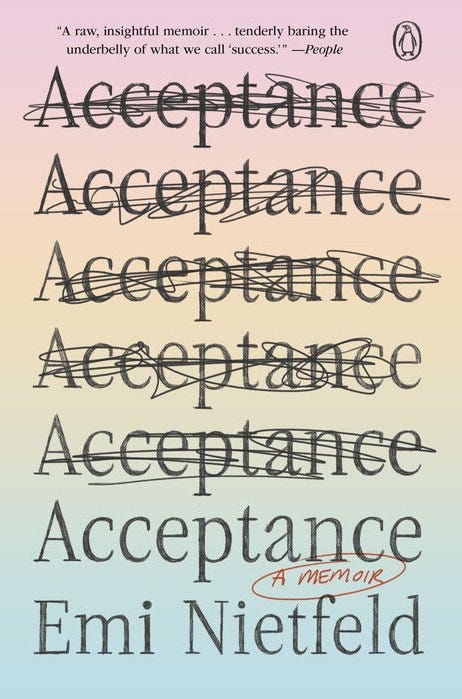

Today, I started on Accepted by Emi Nietfeld, one of the books that have been recommended to me the most. I’m not too far into it, but I have a feeling it’ll resonate with me. Nietfeld — a former foster youth, Harvard graduate, and software engineer with Google — talks about society’s obsession with resilience, as well as the myriad hidden costs associated with upward mobility. I’ll let ya know what I think!

What’s going on in the world of child welfare?:

U of I-led Project to Assess Whether Financial Help Prevents Repeated Child Maltreatment (University of Illinois) — An interesting article that aligns directly with my own interests: finding more effective ways to prevent child maltreatment.

How Many Foster Kids Are Homeless in L.A. County? Nobody Knows. (Los Angeles Times) — A lawsuit alleging that LA County is failing to provide stable housing and mental health services for older foster youth.

Exposing the Lifelong Invisibility of Asian and Pasifika Foster Children (AsAm News) — There are so few AAPI children in foster care that their stories often aren’t told. This article seeks to address that.

A Second Chance for MN Moms Who’ve Already Lost Kids to CPS (The Imprint) — A program in Minnesota is offering assistance to expecting mothers, with the goal of preventing the removal of their child following birth.

Thousands of Foster Children Could Lose Their Homes if California Doesn’t Pass This Law (Sacramento Bee) — A well-intentioned policy is threatening thousands of foster homes in California.

Why WA’s Foster Care System is Shrinking Fast (Seattle Times) — Washington’s foster care population has dropped nearly in half in the last six years, and this article explores why.

Death of 17-year-old Foster Child Living at Hotel Represents Oregon’s ‘Systemic Failures’ (Oregon Live) — A tragic story underscoring the tragic consequences of using hotels to house children.

Foster Youth Aging out of System Nationwide Get Help from Southwest Montana Nonprofit (KXLF Butte) — A great demonstration of the potential of AI to help foster youth!