Why I Wanted to Study The UK Child Welfare System

How the Tantalizing Prospect of Reform Brought Me Across the Pond

(Click here to access the website version of this newsletter.)

First things first: this will be a two-part newsletter. This week, I have my end-of-the-year exams, so I won’t be doing my customary deep dive on a topic. Instead, I’ll talk a bit about my journey to the UK, and for my next post, I’ll discuss what I’ve learned so far about the child welfare system on this side of the Atlantic.

So, let us begin this newsletter with a question that I was asked as I prepared to interview for the Marshall Scholarship:

“Why do you want to study the UK’s child welfare system? Their system is so much worse than ours!”

The man who asked this question is considered a leading expert on the US child welfare system, whose name is almost universally known amongst people who work in this space. I had specifically chosen him to participate in a mock interview because I knew he’d ask some hard-hitting questions, and I was very grateful that he accepted. What I didn’t expect was that he’d lead with one of the hardest questions I’d been asked up to that point.

For folks who don’t know, the whole purpose of the Marshall Scholarship is to strengthen the relationship between the United States and the United Kingdom. Applicants are expected to present ideas on how they specifically intend on doing this, using their respective fields as the vehicle to contribute to this Special Relationship. So, a question with the premise that the UK child welfare system is worse than the US’s posed some challenges.

But my interest in studying in the UK was not to glean insights into how it was currently functioning but rather how it might function in the years to come. Let me rewind a bit.

Around May 2022, I had just wrapped up what I considered my academic magna opus at the time: a 15-page memo arguing for the passage of a hypothetical Family First Preservation Act. In this memo, I marshaled all the available evidence to argue for radical reform in our approach to child welfare, mainly by providing economic and financial support to at-risk families, and to provide this support as early as humanly possible. The name of this hypothetical legislation, of course, stems from the Family First Prevention Services Act, passed in 2018, which was a great but insufficient first step in keeping families together (more on that in a future newsletter).

To be clear, this memo wasn’t exactly groundbreaking. I wasn’t saying anything that hadn’t already been said, nor was I advancing any novel arguments. Rather, this was the first time that I put it all together in one place, and by “it” I mean my grand vision for the child welfare system in the United States: a system that protects children, keeps families together, and heals communities.

Shortly after this, however, I realized I knew next to nothing about how other countries approach this wickedly complex issue. Does the system I imagine even exist? Are there any countries that are protecting children and preserving families, or possibly protecting children by preserving families? And if so, how do they do it?

So I set my sights abroad and started doing some research. Naturally, one of the first countries I looked at was the United Kingdom. I knew a good bit about the country’s recent political history and some basic facts about its broader history, but I knew nothing about its child welfare system. My timing was fortuitous, however, because right around the time I was doing this deep dive, I stumbled upon a very promising report: the Independent Review of Children’s Social Care (children’s social care is what the UK calls its child welfare system). To be clear, this review focused strictly on England, though other countries in the UK have conducted reviews of their respective systems as well.

Put simply, this report calls for a ‘radical reset’ in children’s social care. It recommended a series of transformative reforms — from providing quick and effective help to families (Family Help) to revitalizing the children’s social care workforce — that would help fix a system that the lead author of the report described as “a 30-year-old tower of Jenga held together with Sellotape: simultaneously rigid and yet shaky.” My overview of these reforms led me to conclude the following: had some of these suggested policies been in place in the US when I was growing up, there’s a dang good chance that I wouldn’t have ever entered the foster care system.

I will briefly discuss some of these of the suggested policy reforms in my next newsletter, but let’s just say some of the momentum this report generated was lost in the midst of the political, social, and economic turmoil that took place at the end of 2022 (when the country cycled through multiple prime ministers, grappled with the national trauma following the death of Queen Elizabeth II, and experienced an economic crisis).

How this report came to be and how it was conducted, however, is just as interesting as the policy recommendations it contained, at least to me.

In 2019, the ruling Conservative Party released its manifesto (its political platform), where it pledged to conduct a review of the country’s children’s social care system. Now, for diplomatic reasons, I won’t wade too deep into other aspects of the Tory’s platform (or the Labour Party’s, for that matter) or comment on the country’s politics, but I found it incredibly encouraging that a major political party would make such a public commitment to a system that can be so often ignored.

For comparison’s sake, I looked at the platforms for both major parties in the United States for every presidential election since 2008 and searched “foster,” and the word was often not used to discuss the child welfare system but rather as a verb, as in, “we will foster innovation.” Don’t get me wrong, there were glancing references to the system and foster children in several of the platforms, but it is clear that addressing the issue was not a priority for either party (Iran was mentioned more frequently than the foster care system in multiple platforms).

The years-long review itself was conducted with active input from people with lived experience in the children’s social care system: birth parents, foster children, former foster youth (“care experienced adults”), foster parents, kinship carers, child welfare professionals, unaccompanied youth seeking asylum, and former foster youth involved in the juvenile justice system (“young care leavers in Young Offender Institutions”).

The folks conducting the review hit the road and traveled around the country, hosted events, and listened to people in multiple local authorities (kind of like counties in the US). They embedded themselves in families, conducting weeks-long ethnographic research. They spoke with charity organizations providing services to those involved in the system and who advocate for change in the system itself. They visited carceral facilities, speaking with mothers who had given birth to their children while in prison. They did all this, and so much more.

Shortly after reading about the Independent Review, I cold emailed some policy advocates who work in London and set up a couple of Zoom interviews. I wanted to see if what I was reading was worth getting excited about, or was I just getting worked up over some banal report. Fortunately, at the time, I found that the folks I spoke with were cautiously optimistic. For battle-hardened policy advocates accustomed to fighting tooth-and-nail for change in a system that often resists change (this description can be applied to people on either side of the Atlantic), this counts as giddy excitement. They still had a “let’s see what happens” mentality, but nevertheless, there was hope. And, for me, hope is an essential ingredient in the fight for progress.

I was (and remain) intrigued by the possibility of seeing the same process play out in the United States. Readers, correct me if I’m wrong, but as far I can tell, a similar-style review has never been conducted on the state or federal level in the United States. Sure, there are several fantastic advocacy organizations that release reports on the state of child welfare, who incorporate the perspectives of those with lived experience, and who sketch out a vision for child welfare reform. I’ve used these reports in several of my writing projects, and I have a handful saved onto my computer at this very moment.

But, to have one of the major political parties commission a review, to empower clear-eyed and passionate advocates to conduct this review, and to provide these reviewers with the resources and support they need? To spend a few years traveling around the country, speaking with the people most impacted by the broken system, and involving all relevant stakeholders in crafting a vision of reform? That may be just what we need in the United States to elevate the issue of child welfare in the national conscience, which is exactly what is required if change is ever to occur.

In the child welfare system, policy is often conducted in an ad-hoc, piecemeal, and reactive fashion. Policymakers ignore the issue for the most part, until an inciting incident (mainly, tragedy) brings this issue to the fore. Instead of reacting to developments, we need a proactive national (and sub-national) child welfare strategy, and to formulate this strategy, we need to have a comprehensive grasp of the issue. This is precisely what a potential Independent Review of the Child Welfare System can provide us.

So, to answer the question that was posed to me all those years ago, the one I mentioned at the outset of this newsletter: my desire to study in the UK stemmed from my interest in potentially watching a new system be born. To see, up close and personal, the gears of policy begin to work for families and children, rather than against them. And, importantly, I wanted to glean insights into how this country managed to inject something into the child welfare policy process that is often absent from it: introspection and humility.

That’s all I have for this week. In just over 48 hours, I have my final exams, so wish me luck with these last few days of studying. In two weeks, I’ll do a deep dive on the UK system, including a bit more on the reforms suggested in the Independent Review as well as an overview of the current challenges plaguing the system.

Until then, please be well, and as always, thank you for reading and subscribing!

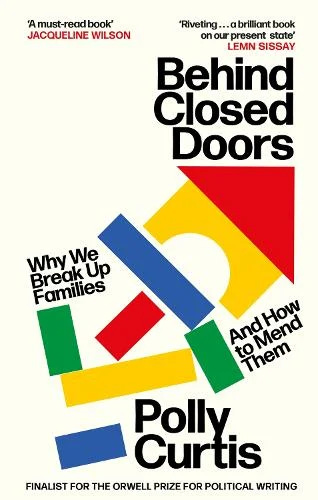

Current Read(s):

In anticipation of this newsletter and the next, I just finished Behind Closed Doors: Why We Break Up Families and How to Mend Them by Polly Curtis. It’s an incredibly moving book that explores the various ways in which the children’s social care system is failing, and the author (a journalist) talks to the people who are being failed the most: mothers, fathers, social workers, and children. Here are some factoids from the book I found interesting, moving, and downright tragic:

“Changes in our collective economic fortunates, public health problems, social norms and political rhetoric all play out in the lives of families and the decisions made by social workers and the courts across the country every day.”

“Across the UK, children are ten times more likely to be in care if they live in the poorest 10% of areas, as opposed to the wealthiest 10%.”

“There are currently nearly 80,000 children in the care system in England. A third of them need never have come to court at all if social services was resourced to focus on this ‘pre-proceedings’ stage. That’s more than 26,000 children who needn’t be in the care system.”

“If the rise of children going into care is a prism through which to assess society, you find it riven with bias about class, disadvantage, and wealth.”

“One in four women who has a child removed through the family courts is likely to return to have another taken away, and that number increases to one in three if they’re a teenage mother. The cycle of child removal is even more intense if a parent has been in care themselves: four out of ten women who have multiple children removed grew up in care.”

What’s going on in the world of child welfare?:

Podcast Gives Former Foster Youths a Voice. They have Lots to Discuss (Washington Post) — The best way to learn how the foster care system works is to listen to the folks who lived in it, and a group of former foster youth have a podcast that allows you to do just that: listen. Better yet, if you are a former foster youth yourself, this is the podcast for you, because ‘Self-Taught’ has been described as a podcast “by and for” former foster youth. Here’s a link to the podcast on Spotify.

Former Foster Youth Are Eligible for Federal Housing Aid. Georgia Isn’t Helping Them Get It (ProPublica) — On several fronts, Georgia just can’t seem to get housing right for children and families involved in its child welfare system. This is one of the more egregious examples of this failure: Georgia could get free federal housing aid for former foster youth but are just failing to do so.

AG Mayes Seeking Criminal Investigation for Foster Group Home Tied to Gov. Hobbs (ABC 15 Arizona) — A little ‘pay-to-play’ action might be taking place in Arizona. After Sunshine Residential Homes (a state-contracted group home service) donated to Gov. Hobbs and the Arizona Democratic Party, it received a roughly 60% pay rate increase. The Governor’s office denies any impropriety, and I will eagerly await the results of this investigation.

As Budget Deadline Looms, California’s Child Welfare System Slated for Deep Cuts (The Imprint) — My beloved home state is decimating some of the most essential services for foster youth as a result of the state’s budget crisis, and its breaking my heart. From essential preventative services to “a special hotline for foster youth in crisis,” everything is on the chopping block. Many children and families lives will be forever changed as a result of the budget debates taking place in Sacramento.

‘I Feel Like a Typical Student’: How DU’s Colorado Lab Is Revolutionizing Education Attainment for Students in Foster Care (University of Denver) — A new program is helping foster youth overcome barriers to getting their education.

‘Pitting One Group Against Another’: Tennessee Asks Disabled Adults to Make Way for Foster Kids (Tennessee Lookout) — Wow. Read this story, please. Two vulnerable groups are being pitted against one another in Tennessee, an example of how one system in crisis can spill over and adversely impact other systems.

Legislation to Reform New York’s Child Welfare System Fares Poorly This Session (The Imprint) — From reforming its reporting system to requiring CPS workers to provide parents a Miranda-style recitation of their rights during child maltreatment investigations, several very promising bills that would improve the lives of families in New York unfortunately did not pass.

For Years, Mothers Were Reported to DCF Simply For Taking Addiction Medication. Massachusetts Lawmakers Are Seeking to End That (Boston Globe) — Efforts are underway in Massachusetts to “free doctors, hospital officials, and others from requirements to report suspected child abuse…solely because a baby is born exposed to drugs.” This includes drugs often prescribed to treat opioid abuse disorder, which should help mothers who previously stopped taking this medication in fear of being reported to CPS.

What You Need To Know About West Virginia’s Child Welfare Crisis (Mountain State Spotlight) — I’ve written in this section previously about the mounting child welfare crisis in the Mountain State, and this article provides a pretty deep and damning overview of state’s many challenges.

Chronic Absenteeism Should Be Investigated Outside Child Welfare System, Lawmakers Told (Nevada Current) — Folks in Nevada are asking the state to find other ways to hand chronic absenteeism, instead of calling CPS when a kid misses school too many times. Like many states, CPS caseworkers are overburdened with too many reports, and child welfare leaders in the state argue making this switch can take one more thing off their plate.

The Latest Constitutional Challenge to Indian Child Welfare Act is Struck Down in Minnesota Appeals Court (MPR News) — Every year now, it seems, the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) is under attack. The latest — but certainly not the last, as the lawyer behind the challenge vows “fight on” — attack on one of the most child welfare laws in the US has fortunately been struck down.

Congressional Lawmakers Seek Stricter Enforcement of the Indian Child Welfare Act (The Imprint) — . A bipartisan effort in Congress is seeking to “shore up any weaknesses” with ICAW, so that states can better support indigenous children and families.

Senate Report Says US Taxpayers Help Fund Residential Treatment Facilities that Put Vulnerable Kids at Risk (OPB News) — A report by the Senate Committee on Finance and the Senate Committee on Health Education, Labor and Pensions highlighted “rampant civil rights rights” abuses in residential treatment facilities.

Texas’ Attempt to Remove Federal Judge from Overseeing Foster Care Called ‘Cynical’ (Texas Public Radio) — Like many states, Texas has been struggling mightily with its child welfare system, and this article highlights a few of the most recent developments in a years-long effort by a federal judge to get the system on track.

Wow. This is a wondeful newsletter. Thank you so much. And good luck on your examines, although I'm sure you will ACE them all. 👍👍

"And, for me, hope is an essential ingredient in the fight for progress." - INCREDIBLE! That really stuck with me.

Good luck on your exams!